By Peter Dekker, August 26, 2012

Composite bow making is a complex art, one works with various materials like horn, sinew, and wood, all held together by natural glue made of fish bladders. In the bow's operation, considerable forces will be exerted on the materials and their connections. At the same time, the bow's efficiency into transferring its stored energy into the arrow relies on its tips being as light as possible. one can see the challenge here, a good bowyer needs to know his materials and bonding agents through and though to construct tips that are just able to handle the stresses of the pull and release, while minimizing the weight of all parts for maximum efficiency. Vital to this art is the ability to make strong yet lightweight ears and knees, which is typically accomplished with a series of deep V-splices that require a high level of precision. The Manchu bow, along with the north Indian "crab" bow, is among the more challenging of composite bow designs to make. Not only because the long ears require more precision in workmanship than shorter eared bow designs for the ears to be in perfect alignment, the lever action of the long ears will also exert more force on the knee joint. Therefore only few today make good traditional composite Manchu bows, Wen Chieh Huang from Taiwan is one of those bowyers. This article is written to give some insight into the construction of a Manchu bow.

The bowyer

An amateur

taxidermist with a love for craftsmanship, Wen Chieh picked up bow making only

recently but quickly proved himself to be among the very best. When I first saw

a bow by his hand it was like coming home: "This is how they used to do

it" was the first thing that sprang my mind. In terms of design his bows

compare well with some of the better antique bows I've examined. Wen Chieh also

developed himself as a restorer, having brought various old bows back in

shooting condition. He kindly granted permission to use his pictures for this

article.

Materials

Manchu bows

are made around a core of wood or bamboo. Bow cores were described as being made

of various types of wood like mulberry, birch, elm or bamboo. The rigid ears

could be made of sandalwood, birch, mulberry, acacia, elm, or other woods.

Imperial bows are described being built with a mulberry core with ears made of

sandalwood.1 In the Changxing workshop in Chengdu

they used a species of large bamboo for the core, with ears made of mulberry and

sandalwood.2 The belly side of the bow is

reinforced with horn, most commonly of the Chinese waterbuffalo. The back side

is covered with sinew, often from a buffalo's back. The outer limbs in turn are

covered with birch bark to protect the moist-sensitive sinew. String birdges are

made of wood, bone, horn or deer antler. To finish the bow the handle is usually

covered with cork, on some bows other types of bark and ray-skin complement the

outer finish. Ray-skin is highly abrasion-resistant and was used parts that were

rubbed by string or arrow such as the ears and near the handle. Depending on the

purpose of the bow, were made of silk, gut, strips of deerskin, hemp, or cotton.

All parts are held together with fish bladder glue.

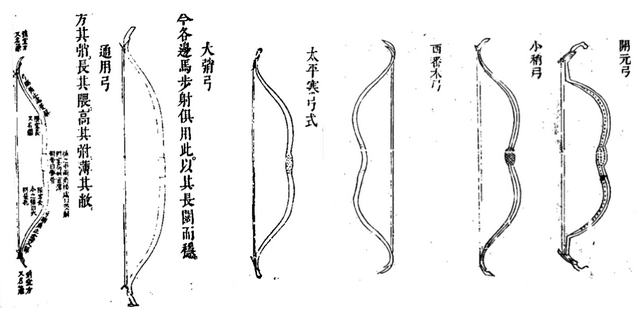

1Pu Jiang

et al., eds., 皇朝禮器圖式, Huangchao Liqi Tushi, Palace Edition of 1766 (British

Library, 15300.e.1). Based on a manuscript of 1759.

2Tan Danjiong (T'an Tan-Chiung), INVESTIGATIVE REPORT on BOW

AND ARROW MANUFACTURE IN CHENGTU, Soochow University Journal of Chinese Art

History Vol. XI. 1981.

The building process

Various bow-making materials. To make a Manchu bow,

one needs horn plates of at least 55 cm in length.

Two ears spliced into their knee

pieces. These knees are referred to as 腦 in Chinese, literally the "brain" of

the bow.

A prepared core ready to have its

ears attached.

A finished core. All parts need to

be in perfect alignment, which with so many splices is quite a feat.

Attaching the handle section. Note

that the previous bow had v-splices at the handle. Usually the core was one

piece, with a separate

piece of wood glued on at the handle.

Expertly executed v-splices.

On many bows a separate piece of

horn was spliced in to reinforce this part

On some bows, the core surface is

convex fitting in a concave piece of horn. It is a lot of work but results in a

better quality bow that is

somewhat less prone to twist.

The belly side of the core is

scored to increase the surface for glueing.

And the horn is scored as well.

Prepared fish bladder, with the

actual bladders on the right. Making and using this glue is an art in itself,

the right consistency is vital for the

quality of the finished product. Despite this, it is the best glue for the job with great adhesive strength and flexibility. It is also completely reversible,

making the restoration of broken

bows possible.

The belly of the core is covered

with glue, as is the horn, before the two are joined.

Two bow cores with added horn. The

next step is adding the sinew fibers, which are combed and soaked with glue

before being applied to the

core in several layers. Sinew is incredibly strong

and one of the main sources of the power of these bows.

Two bows with sinew applied.

Two bows with sinew applied. Note

that a separate insert is used between the two slabs of horn on the belly. This

piece is often horn, or sometimes bone.

The bow on the left is made with rare

translucent horn, a material highly prized for its beauty.

As the sinew dries, it contracts,

bringing the bow further into a c-shape. To make an efficient Manchu bow it is

important to build it in a deep C in order to stress the limbs to their full

potential when the bow is drawn. Bows that are built with a more straight

profile are weaker for their mass but also somewhat less prone to twist, making

them more foolproof than the high efficiency Manchu bows.

String bridges are added. In this

case one made of deer antler. It uses the spongy part as the inside of the

bridge, this helps reduce the weight. Good bow ear design is all about weight

reduction and Wen Chieh really knows how to keep the weight of the long ears and

sturdy knees to a minimum, which contributes greatly to the bow's efficiency

Two finished bows, strung. The only

thing that remains now is the decoration.

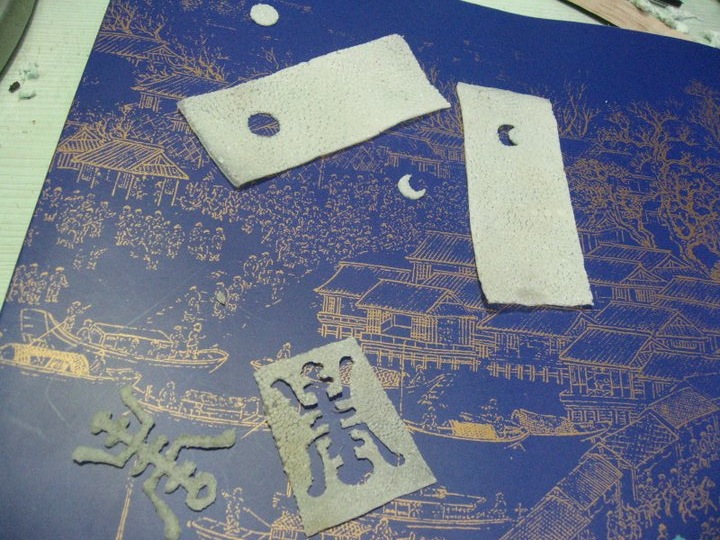

Cutting the ray-skin inlays.

Finished result on the knee.

Handle section with sun and moon

inlaid in ray-skin. This is exactly like an antique bow.

The decoration on these bows are

completely in line with Qing dynasty design and aesthetics.

For my bow I requested that he

based the design on early Manchu bows with irregular tiger stripe patterns. He

did a wonderful job.

Some finished bows

Two finished bows, in the style of

bows of the late 18th through 19th centuries. Very true to the originals,

excellent work.

One of my own bows, made by Wen

Chieh, with white horn belly.

The splices can be seen through the

translucent horn.

An 82 pound Manchu bow Wen Chieh

made for me in the style of early imperial Manchu bows. This was closely based

on a bow owned by the Yongzheng emperor

The graceful lines of the ear of

the same bow. Covered with birch bark, just like the original. Everything is

accurate, up to the

placement of the seams between the sheets and the

orientation of the grain of the bark.

The bow with white horn belly strung.

I hope you enjoyed reading this article! Those who want to attempt to make their own bows, INVESTIGATIVE REPORT on BOW AND ARROW MANUFACTURE IN CHENGTU by T'an Tan-Chiung is an excellent book that provides us with valuable details on late Qing bow making. Another good book on composite bow making is OTTOMAN TURKISH BOWS by Adam Karpowicz, although the shape of the Ottoman bow is different the methods of its construction are very similar.